Bundlers: The Duct Tape Holding the Web Together

I still have nightmares about <script> tags. You know the drill. You load jQuery, then a plugin, then your app logic, and you pray the network requests finish in the exact order you wrote them in the HTML. If they didn’t? Uncaught ReferenceError: $ is not defined. Game over.

That was my life for years. We fixed it with task runners like Grunt and Gulp, stitching strings together into one massive app.js file. It was ugly, but it worked. Until it didn’t.

Fast forward to today, January 2026. The tooling is infinitely better, but also infinitely more complex. We treat bundlers like black boxes. We feed them React, Vue, or Svelte files, and out pops a highly optimized dist folder. But honestly? If you don’t know what’s happening inside that black box, you’re going to hit a wall eventually. Usually at 4 PM on a Friday when a deploy fails.

It’s Just a Graph (Mostly)

At its core, a bundler isn’t doing magic. It’s building a dependency graph. It starts at your entry point (usually index.js or main.ts) and reads the file. It looks for import or require statements, resolves those paths, reads those files, and repeats the process until it has mapped out every single piece of code your application touches.

Here is where people get confused. They think bundling is just concatenation. It’s not. It’s encapsulation.

If you just glued two files together, variables from file A would leak into file B. Chaos. Bundlers wrap modules in functions to create artificial scopes. I once tried to write a “bundler” from scratch for a hackathon—bad idea, by the way—and the hardest part wasn’t reading the files; it was injecting the runtime that makes the browser understand the module system.

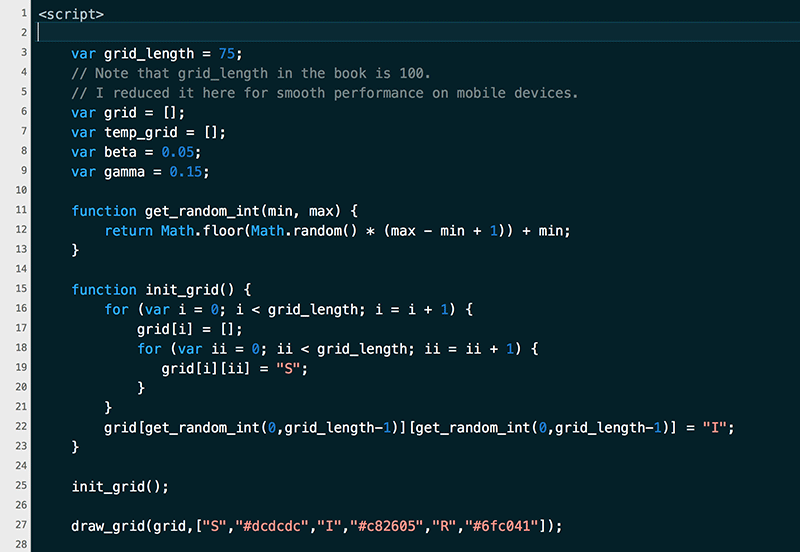

Here is a simplified version of what a bundler actually outputs. You’ve probably seen this in your source maps and ignored it:

// The "Runtime" or "Bootstrap" code

(function(modules) {

var installedModules = {};

// The require function injected into every module

function __my_bundler_require__(moduleId) {

// Check if module is in cache

if(installedModules[moduleId]) {

return installedModules[moduleId].exports;

}

// Create a new module (and put it into the cache)

var module = installedModules[moduleId] = {

i: moduleId,

l: false,

exports: {}

};

// Execute the module function

modules[moduleId].call(module.exports, module, module.exports, __my_bundler_require__);

// Flag the module as loaded

module.l = true;

// Return the exports of the module

return module.exports;

}

// Load entry module and return exports

return __my_bundler_require__(0);

})

([

/* 0: main.js */

(function(module, exports, __my_bundler_require__) {

var math = __my_bundler_require__(1);

console.log("2 + 2 =", math.add(2, 2));

}),

/* 1: math.js */

(function(module, exports) {

exports.add = function(a, b) { return a + b; };

})

]);See that? That’s the secret sauce. The browser doesn’t see your files; it sees an array of functions and a bootstrapper that manages them.

The Performance Obsession

Why do we still do this in 2026? Browsers support ES Modules natively now. We could just use <script type="module"> and let the browser fetch everything. I tried this on a small side project last year. It felt great in development—no build step!

Then I looked at the network tab.

My simple app was making 400 separate HTTP requests. Even with HTTP/3, the waterfall was brutal. The latency killed the load time. Bundling is still necessary because fetching one 50KB file is vastly faster than fetching fifty 1KB files.

But here is the catch: if you bundle everything into one file, you block the main thread. The user stares at a white screen while your 5MB JavaScript blob downloads and parses. I’ve been guilty of this. “Just ship it,” I said. “Internet is fast now,” I said. Users on 4G networks disagreed.

Code Splitting is Your Best Friend (Sorry, I Had to Say It)

Okay, I won’t call it your best friend. But it’s the one feature you actually need to understand manually. Most bundlers are smart, but they aren’t psychic. They don’t know that your “Admin Dashboard” component is only visited by 1% of your users.

You have to tell them.

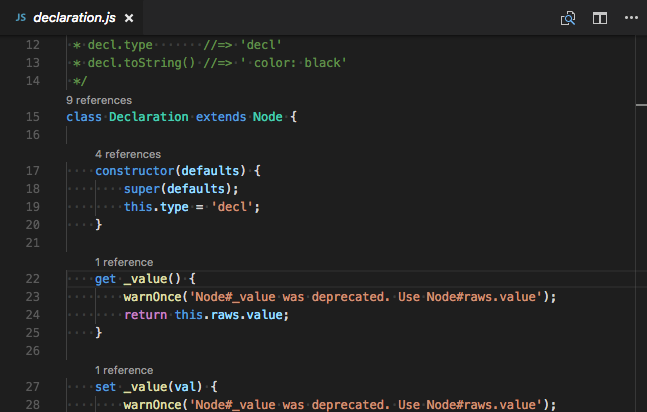

This is where dynamic imports come in. It stops the bundler from including the code in the main bundle and instead creates a separate “chunk” that loads on demand. It looks like this:

// Don't do this at the top level if you don't need it immediately

// import HeavyChart from './HeavyChart.js';

document.getElementById('load-chart-btn').addEventListener('click', async () => {

try {

// This tells the bundler: "Split this file out!"

const module = await import('./HeavyChart.js');

const HeavyChart = module.default;

const chart = new HeavyChart();

chart.render(document.body);

} catch (err) {

console.error("Chunk failed to load", err);

}

});When the bundler sees import() used as a function, it halts. It says, “Okay, I’m cutting the graph here.” It creates a new file (e.g., chunk-732.js) and leaves a reference in the main bundle to fetch it later.

I messed this up recently. I was dynamically importing a library, but I accidentally included a static reference to it in a utility file. The bundler saw the static reference, assumed I needed it everywhere, and pulled the whole thing into the main bundle. The dynamic import became useless. Always check your bundle analyzer.

Tree Shaking: The Lie We Tell Ourselves

We love the term “Tree Shaking.” It sounds so clean. You shake the tree, and the dead leaves (unused code) fall off.

In reality, it’s more like a cautious gardener with a pair of dull scissors. JavaScript is a dynamic language. It’s really hard for a static analysis tool to be 100% sure a piece of code is never used. If you have a function with side effects—like modifying a global variable—the bundler has to keep it, just in case.

To help the bundler, you need to write “pure” code. If I write this, the bundler can’t remove it safely:

// bad-module.js

const cache = {};

function store(key, val) {

cache[key] = val; // Side effect! Modifying outer scope

}

export function unusedFunction() {

store('test', 123);

}Even if I never import unusedFunction, the bundler might keep the file because executing the file creates that cache object. It doesn’t know if some other part of my app relies on that side effect. Most modern tools (like the ones we use now in 2026) are better at detecting this via package.json “sideEffects”: false flags, but it’s not foolproof.

The State of Things in 2026

I used to spend days configuring Webpack. Now? I mostly use Vite or tools built on top of Rolldown. The shift to Rust-based tooling (and Go) has made everything absurdly fast. I remember waiting 40 seconds for a dev server to start in 2018. Now if it takes more than 400ms, I assume something is broken.

But speed isn’t everything. The complexity has just moved. Instead of configuring loaders, we’re configuring plugins to handle edge cases between our Rust bundler and our legacy Babel transforms. It’s a different kind of headache.

So, what’s the takeaway? Stop trusting the defaults blindly. Open up that dist folder. Look at the generated code. Is it creating 50 chunks for a generic landing page? Is it bundling Lodash three times? (Yes, that still happens). The tools are smarter, but they still need a human pilot.