Private Fields Finally Made Me Respect JavaScript Classes

Actually, I should clarify – I resisted JavaScript classes for years. Seriously. I was that guy in code reviews leaving comments like “why not just use a factory function and a closure?” whenever I saw the class keyword. It felt like we were pretending to be Java developers while running on a prototype-based engine that didn’t actually care about our architectural feelings.

But things shifted. It wasn’t overnight, and it definitely wasn’t because I suddenly learned to love inheritance (I well, that’s not entirely accurate – I still think inheritance is usually a trap). It was the stabilization of private class features—specifically private fields and methods—that finally gave classes a reason to exist in my toolkit beyond just “React components used to need them.”

If you’re still writing _internalProperty and hoping nobody touches it, you’re doing it wrong. And it’s 2026. We have real privacy now.

The Hash Syntax is Ugly, but It Works

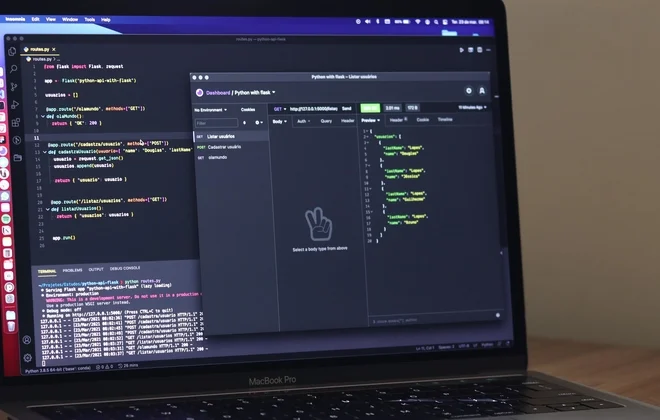

Let’s address the elephant in the room. The # syntax looks weird. Probably when it first landed, I hated it. It looked like a Ruby comment had crashed into my JavaScript. But after using it in a large-scale Node.js 25.1 project last month, I stopped caring about the aesthetics because the functionality is rock solid.

Unlike TypeScript’s private keyword, which is just a compile-time suggestion that vanishes at runtime, JS runtime private fields are actually private. You can’t inspect them from the outside. You can’t accidentally mutate them. They are locked down.

Here is a practical example of an API client that handles token rotation. In the old days, I would have used a closure to hide the token. Now? A class is actually cleaner.

class SecureApiClient {

// Private fields must be declared upfront

#apiKey;

#baseUrl;

#requestCount = 0;

constructor(baseUrl, key) {

this.#baseUrl = baseUrl;

this.#apiKey = key;

}

async fetchResource(endpoint) {

this.#incrementUsage();

try {

const response = await fetch(${this.#baseUrl}/${endpoint}, {

headers: {

'Authorization': Bearer ${this.#apiKey},

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

}

});

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(HTTP Error: ${response.status});

return await response.json();

} catch (error) {

console.error(Request failed: ${error.message});

throw error;

}

}

// Private method - cannot be called from outside

#incrementUsage() {

this.#requestCount++;

if (this.#requestCount > 1000) {

console.warn('Rate limit warning: approaching 1000 requests');

}

}

// Public getter to safely expose read-only data

get usageStats() {

return { requests: this.#requestCount };

}

}

// Usage

const client = new SecureApiClient('https://api.example.com', 'secret_123');

// client.#apiKey // SyntaxError: Private field '#apiKey' must be declared in an enclosing classThe beauty here is hard encapsulation. If I hand this client instance to a third-party library or a sloppy junior dev, I know for a fact they cannot scrape the API key or mess with the request counter. It’s physically impossible within the language runtime.

Managing DOM State Without the Spaghetti

Another place where I’ve started defaulting to classes is complex DOM manipulation. I know, frameworks usually handle this, but sometimes you’re building a vanilla widget or a Web Component and you need to keep state synced with the UI.

I recently refactored a drag-and-drop uploader. The previous version attached state directly to DOM nodes (element.isUploading = true), which is a pretty much a recipe for disaster. Using a class with private state keeps the DOM dumb and the logic contained.

class UploaderWidget {

#element;

#files = new Set();

#isUploading = false;

constructor(selector) {

this.#element = document.querySelector(selector);

if (!this.#element) throw new Error('Element not found');

this.#init();

}

#init() {

// Arrow function automatically binds 'this' to the class instance

this.#element.addEventListener('click', () => this.#handleClick());

this.#element.addEventListener('drop', (e) => this.#handleDrop(e));

this.#render();

}

async #handleClick() {

if (this.#isUploading) return;

console.log('Opening file dialog...');

// Mocking file selection

await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 500));

this.#files.add(file_${Date.now()}.png);