Browser Compute Clusters: Why I Stopped Paying for Cloud GPU

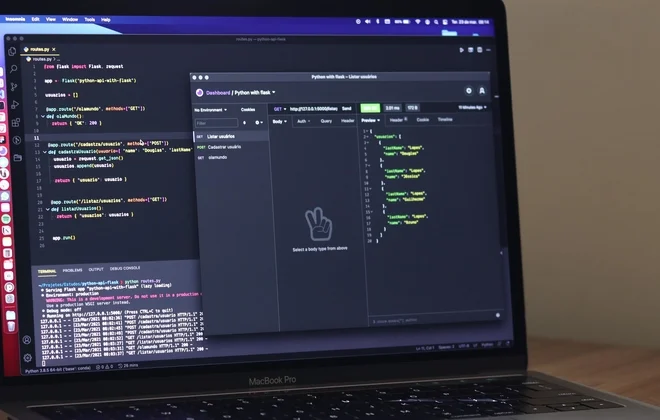

I looked at my AWS bill last month and almost threw up. It wasn’t even a complex project—just some basic inference tasks for a side project I’ve been hacking on. But GPU instances are expensive, and keeping them running 24/7 for a service that only gets sporadic traffic feels like burning money in a barrel.

Then I looked at the laptop I was working on. It’s got a GPU that sits idle 90% of the time. The phone in my pocket? Same deal. The tablet my kid uses to watch Minecraft videos? Surprisingly capable silicon.

We’ve been talking about “edge computing” for years, but usually, that just means “CDNs doing a bit more logic.” But recently, I’ve been obsessing over a different angle: browser-based heterogeneous computing. Specifically, using WebGPU to turn a mesh of connected users into a distributed supercomputer.

Sound crazy? Maybe. But I’ve been testing this out, and honestly, the performance numbers are starting to make my cloud provider look like a scam.

The GPGPU Nightmare is Finally Over

If you tried to do general-purpose computing on the web five years ago, you probably have the same scars I do. We had to trick WebGL into thinking our data was pixels. You’d encode a physics simulation into a texture, render a “frame” that was actually just math, and then read the pixels back. It was janky, fragile, and debugging it made me want to quit tech and become a goat farmer.

WebGPU changed that. By now, in late 2025, support is solid across the board. We aren’t hacking triangles anymore. We have legitimate Compute Shaders. We have storage buffers. We have low-level access that feels suspiciously like Vulkan or Metal, but inside Chrome or Safari.

The cool part isn’t just that we can do it. It’s that we can do it asynchronously while the main thread handles the UI. This is true heterogeneous computing—CPU handles the logic and networking, GPU chews through the parallel grunt work.

Building the Mesh

Here’s the architecture I’ve been playing with. It’s not ready for production (please don’t put this in your banking app), but it works.

The idea is simple: You have a “Host” (the user needing work done) and “Peers” (other users on the site). Using WebRTC data channels, you build a mesh. The Host chunks up a massive dataset—say, training a small model or running a fluid sim—and blasts these chunks to the Peers.

The Peers receive the data, dump it into a WebGPU buffer, run a compute shader, and fire the results back.

I wrote a quick test to see how hard the setup actually is. The WGSL (WebGPU Shading Language) side is surprisingly readable compared to the old GLSL mess.

// The Compute Shader (WGSL)

const shaderCode =

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read> inputBuffer : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> outputBuffer : array<f32>;

@compute @workgroup_size(64)

fn main(@builtin(global_invocation_id) global_id : vec3<u32>) {

let index = global_id.x;

// Guard against out of bounds

if (index >= arrayLength(&outputBuffer)) {

return;

}

// Heavy math operation simulating work

let val = inputBuffer[index];

outputBuffer[index] = val * val + sin(val) * cos(val);

}

;

// The JavaScript setup (simplified)

async function initCompute(device, inputData) {

const module = device.createShaderModule({ code: shaderCode });

// Create pipeline

const pipeline = device.createComputePipeline({

layout: 'auto',

compute: { module, entryPoint: 'main' }

});

// ... Buffer creation and bind group setup logic goes here ...

// I'm skipping the boilerplate because it's verbose, but you get the idea.

const commandEncoder = device.createCommandEncoder();

const passEncoder = commandEncoder.beginComputePass();

passEncoder.setPipeline(pipeline);

passEncoder.setBindGroup(0, bindGroup);

passEncoder.dispatchWorkgroups(Math.ceil(inputData.length / 64));

passEncoder.end();

device.queue.submit([commandEncoder.finish()]);

// Read back results...

}That code runs on the client. It’s fast. On my mid-range laptop, I can crunch millions of data points in milliseconds. Now imagine scaling that across 50 connected users.

The “Why Would Anyone Do This?” Question

I know what you’re thinking. “Why rely on random users’ browsers when I can just pay for reliability?”

Two reasons: Cost and Latency.

If you’re building a collaborative tool—think Figma for 3D rendering or a multiplayer physics sandbox—round-tripping to a server for physics calculations is too slow. You want the simulation to happen right there. But if the simulation is too heavy for one machine, sharding it across the other participants in the room is a brilliant workaround. You get a distributed physics engine for free.

Also, have you seen GPU pricing lately? Even with the market stabilizing a bit in late 2025, it’s not cheap. Offloading compute to the edge is basically free infrastructure, provided you can handle the coordination headaches.

The Ugly Parts (Because There Are Always Ugly Parts)

It’s not all sunshine and free teraflops. I ran into some serious walls while prototyping this.

1. Synchronization is hell.

When you distribute work to 10 peers, one of them will be on a potato phone with 10% battery. They will lag. If your simulation depends on their result for the next frame, your whole mesh stutters. I had to implement a speculative execution model where the host guesses the result if a peer is too slow, then corrects it later. It’s messy logic.

2. Browser Tabs throttling.

If a user switches tabs, browsers (rightfully) throttle the JS thread. Your compute shader might still run fast, but the WebRTC coordination code slows to a crawl. I had to use Web Workers to keep the heartbeat alive, and even then, Safari is… well, Safari.

3. Security.

You are executing code on someone else’s GPU. While WebGPU is sandboxed, the potential for side-channel attacks or just annoying the user by draining their battery is real. You have to be ethical here. I added a “Power Saver” toggle that checks the Battery Status API and disables peer compute if the user isn’t plugged in.

What’s Next?

I’m currently rewriting my relay server to handle dynamic peer discovery better. The goal is to have a swarm where nodes can drop in and out without the calculation crashing.

The web platform has finally caught up to the hardware. We have the pipes (WebRTC) and the engine (WebGPU). The only thing missing is the software layer to glue it all together easily. I suspect by mid-2026, we’ll see a major framework emerge that does for browser-compute what React did for UI.

Until then, I’ll keep hacking on my custom implementation. It’s janky, it breaks if I close the lid, but watching a fluid simulation run across three different laptops on my desk without a server is the kind of tech magic I haven’t felt in a long time.