Stop Over-Engineering: Why I Returned to Vanilla JS for My Latest PWA

I stopped building native apps for simple utilities about two years ago. I used to reach for React Native or Flutter immediately when I had an idea for a small tool, like a unit converter or a secure token generator. But recently, while debugging a heavy build pipeline that was taking longer than the actual coding session, I hit a breaking point.

Why was I downloading 400MB of dependencies to render three input fields and a button?

I decided to strip it all back. No build steps, no complex frameworks, just HTML, CSS, and modern JavaScript. The goal was simple: build a “LocalSecure Token Generator”—a tool to create cryptographically strong passwords that runs entirely in the browser, works offline, and installs on my phone just like a native app.

The result? It loads in under 100 milliseconds, works perfectly in Airplane Mode, and the entire codebase is smaller than a single typical npm package logo. Here is how I built it and why I think the Progressive Web App (PWA) standard combined with modern ES2025 JavaScript is the actual “write once, run anywhere” dream we were promised.

The “App” Illusion: The Manifest File

The difference between a website and an app often comes down to the browser chrome—the URL bar, the back button, the browser menus. To get rid of that, I didn’t need a compiler; I just needed a manifest.json.

This JSON file tells the browser, “Hey, treat me like a first-class citizen.” I see a lot of developers overcomplicate this, but for my token generator, I kept it minimal.

{

"name": "LocalSecure Token Gen",

"short_name": "TokenGen",

"start_url": "/index.html",

"display": "standalone",

"background_color": "#1a1a1a",

"theme_color": "#00ff88",

"icons": [

{

"src": "icon-192.png",

"sizes": "192x192",

"type": "image/png"

},

{

"src": "icon-512.png",

"sizes": "512x512",

"type": "image/png"

}

]

}The key property here is "display": "standalone". This removes the browser UI. When I launch this from my home screen, it looks and feels native. It occupies the full screen, and on mobile, it separates itself from the browser instance in the task switcher.

Service Workers: The Offline Brain

This is where most people get intimidated, and honestly, I did too for a long time. Service Workers sound complex, but they are essentially just a proxy server that sits between your web app and the internet.

For a utility app that generates passwords or tokens, I don’t want it to fail just because I’m on the subway or my Wi-Fi drops. I want it to be “Local-First.”

I use a “Cache First” strategy for my static assets (HTML, CSS, JS) because they rarely change in a vanilla project. Here is the exact service worker logic I use in sw.js. Note the use of async/await which makes the promise handling much more readable than the older .then() chains.

const CACHE_NAME = 'token-gen-v1';

const ASSETS = [

'/',

'/index.html',

'/style.css',

'/app.js',

'/manifest.json',

'/icon-192.png'

];

// Install event: Cache everything immediately

self.addEventListener('install', (event) => {

event.waitUntil(

(async () => {

const cache = await caches.open(CACHE_NAME);

console.log('[Service Worker] Caching all assets');

await cache.addAll(ASSETS);

})()

);

});

// Fetch event: Serve from cache, fall back to network

self.addEventListener('fetch', (event) => {

event.respondWith(

(async () => {

const cachedResponse = await caches.match(event.request);

if (cachedResponse) {

return cachedResponse;

}

try {

const networkResponse = await fetch(event.request);

return networkResponse;

} catch (error) {

// If offline and not in cache, we could return a fallback page

console.error('[Service Worker] Fetch failed:', error);

}

})()

);

});This code is powerful. Once a user visits my site *once*, the files are stored in their browser. If they turn off their data and refresh, it still loads. It’s instantaneous.

Registering the Worker

To make the service worker run, I need to register it in my main JavaScript file. I usually wrap this in a check to ensure the browser supports the API, though in 2025, support is virtually universal.

// app.js

const registerServiceWorker = async () => {

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

try {

const registration = await navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js');

console.log('Service Worker registered with scope:', registration.scope);

} catch (error) {

console.error('Service Worker registration failed:', error);

}

}

};

registerServiceWorker();I keep this logic at the bottom of my main script or inside a DOMContentLoaded event listener to ensure it doesn’t block the initial render of the UI.

The Core Logic: Web Crypto API

Since this is a security tool, I can’t use Math.random(). It’s not cryptographically secure. A lot of developers immediately npm install a heavy library like uuid or crypto-js here. But the browser has a built-in, incredibly robust tool for this: the Web Crypto API.

It’s native, written in C++ under the hood, and faster than any JavaScript library I could bundle.

Here is how I implemented the token generation logic. I’m using modern arrow functions and DOM manipulation to keep it clean.

const generateSecureToken = (length = 32) => {

const charset = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789!@#$%^&*()_+';

const array = new Uint32Array(length);

// This is the magic line - fills array with cryptographically strong random values

window.crypto.getRandomValues(array);

let token = '';

for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {

token += charset[array[i] % charset.length];

}

return token;

};

// Connecting to the DOM

const generateBtn = document.getElementById('generate-btn');

const outputField = document.getElementById('token-output');

const copyBtn = document.getElementById('copy-btn');

generateBtn.addEventListener('click', () => {

const newToken = generateSecureToken(16);

outputField.value = newToken;

outputField.classList.add('fade-in'); // simple CSS animation trigger

// Remove animation class after it runs so we can re-trigger it

setTimeout(() => outputField.classList.remove('fade-in'), 500);

});

copyBtn.addEventListener('click', async () => {

if (!outputField.value) return;

try {

// Modern Clipboard API

await navigator.clipboard.writeText(outputField.value);

alert('Token copied to clipboard!');

} catch (err) {

console.error('Failed to copy text: ', err);

}

});Notice the use of navigator.clipboard.writeText. This is an async operation that returns a Promise. It’s much cleaner than the old document.execCommand('copy') hack we used to rely on. This is what I mean by Modern JavaScript—the standard library is so rich now that external dependencies are often unnecessary for these types of tasks.

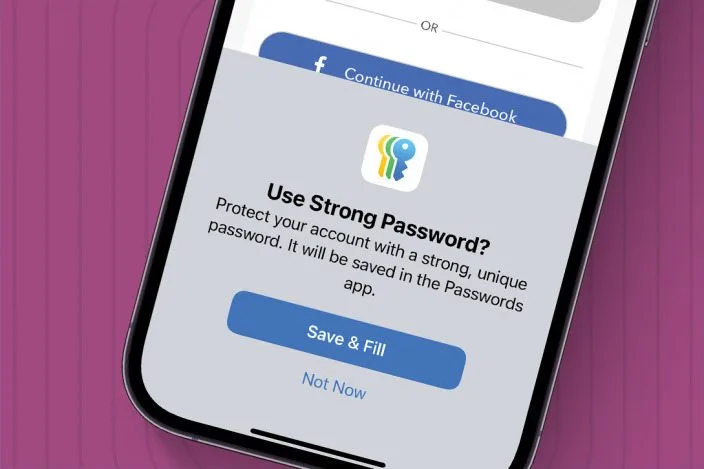

Making It Installable (The “Add to Home Screen” Button)

Browsers will sometimes prompt the user to install the app automatically, but I prefer having a dedicated button in my UI. This gives me control over the experience.

The browser fires a beforeinstallprompt event that we can catch. I save this event and trigger it when the user clicks my custom “Install App” button.

let deferredPrompt;

const installBtn = document.getElementById('install-btn');

// Initially hide the button

installBtn.style.display = 'none';

window.addEventListener('beforeinstallprompt', (e) => {

// Prevent Chrome 67 and earlier from automatically showing the prompt

e.preventDefault();

// Stash the event so it can be triggered later.

deferredPrompt = e;

// Update UI to notify the user they can add to home screen

installBtn.style.display = 'block';

});

installBtn.addEventListener('click', async () => {

// Hide our user interface that shows our A2HS button

installBtn.style.display = 'none';

// Show the prompt

deferredPrompt.prompt();

// Wait for the user to respond to the prompt

const { outcome } = await deferredPrompt.userChoice;

console.log(User response to the install prompt: ${outcome});

deferredPrompt = null;

});This snippet is crucial for user adoption. Instead of hoping the user finds the “Install” option in the browser menu, I put it right in their face (politely). Once installed, the app launches in standalone mode, and the button disappears because the beforeinstallprompt event doesn’t fire in standalone mode.

Handling Data Persistence

Even though my generator is mostly ephemeral, I added a “History” feature so users can see the last 5 tokens they generated. For this, localStorage is perfect. It’s synchronous, simple, and persistent across sessions.

However, since we are dealing with “secure” data, I make sure to clear this history when the tab closes or provide a “Clear History” button. Here is a simple implementation using JSON parsing.

const saveTokenToHistory = (token) => {

let history = JSON.parse(localStorage.getItem('tokenHistory')) || [];

// Add new token to the start of the array

history.unshift({

token,

timestamp: new Date().toISOString()

});

// Keep only the last 5 items

if (history.length > 5) {

history = history.slice(0, 5);

}

localStorage.setItem('tokenHistory', JSON.stringify(history));

renderHistory();

};

const renderHistory = () => {

const historyList = document.getElementById('history-list');

const history = JSON.parse(localStorage.getItem('tokenHistory')) || [];

historyList.innerHTML = history

.map(item => <li>${item.token} <span class="time">${new Date(item.timestamp).toLocaleTimeString()}</span></li>)

.join('');

};

// Call render on load

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', renderHistory);This creates a complete loop: Generate (Web Crypto) -> Display (DOM) -> Save (localStorage) -> Offline Access (Service Worker).

Performance vs. Frameworks

I ran a Lighthouse audit on this finished PWA. The score? 100 across the board. Performance, Accessibility, Best Practices, SEO, and PWA.

When I built a similar tool in React last year, I spent hours tweaking code splitting and lazy loading just to get the bundle size down. With this vanilla approach, my total JavaScript payload is under 5KB. The browser parses that instantly.

I think we often forget that the DOM API has improved drastically. document.querySelector is fast. classList is convenient. Template literals make HTML string interpolation readable. For a single-purpose application, the overhead of a Virtual DOM is simply not worth the cost.

The Security Aspect

One thing I love about this “Local-First” PWA approach is the security narrative. When I share this tool with colleagues, I can tell them: “You can turn off your Wi-Fi before you generate the password.”

Because the Service Worker caches the app logic, they can load the page, kill their connection, and generate tokens. This proves that no data is being sent to a server. It builds immense trust. You can’t easily do that with a server-side rendered app or a cloud-dependent tool.

Why This Matters Now

We are seeing a shift in 2025. The web capabilities are maturing to a point where “Native vs. Web” is becoming a moot argument for utility apps. With Project Fugu APIs expanding what the web can do (file system access, wake locks, etc.), the gap is closing.

But more importantly, user fatigue with app stores is real. I don’t want to go to the store, search, authenticate, download, and install a 50MB app just to generate a password. I want to visit a URL, click “Install,” and be done.

Final Thoughts

Building this PWA reminded me that JavaScript is a powerful language on its own. We don’t always need a build step. We don’t always need a framework. Sometimes, the best tool for the job is the one that’s already in the browser.

If you are looking to build a small utility, I challenge you to try it without your usual stack. Start with an index.html, write a manifest.json, and register a Service Worker. You might be surprised at how refreshing it feels to understand every single line of code running in your application.

The web is capable of amazing things when we stop burying it under mountains of abstraction. My “LocalSecure Token Gen” lives on my home screen now, and I use it almost daily. It never needs an update from an app store, it works in the subway tunnels, and it didn’t cost me a dime in hosting fees. That is the power of a modern JavaScript PWA.