Webpack Compression: How I Slashed My Bundle Size by 80%

I still remember the panic I felt last Tuesday. We were prepping a major release for a client who insists on supporting users in rural areas with spotty 3G connections. I ran the production build, and the main bundle came out weighing a hefty 4.2 MB. In the world of high-speed fiber, that might fly, but for this project? It was a disaster waiting to happen.

We often get so caught up in the latest framework features—whether we’re diving into a React Tutorial or exploring the newest JavaScript ES2024 syntax—that we forget about the physics of the web. Bytes have to travel down wires (or through the air). The more bytes you ship, the slower the experience, and the higher the bounce rate.

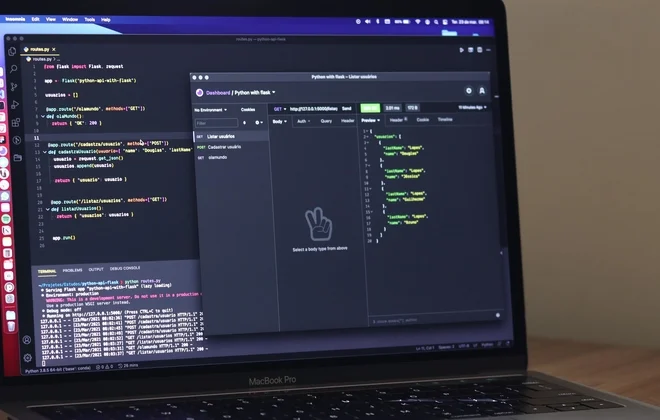

I spent the next few hours tuning our build pipeline. By the time I finished, that 4.2 MB monster was down to a manageable 800 KB, and the compressed transfer size was under 200 KB. The difference in load time was night and day. I want to walk you through exactly how I did it, focusing heavily on compression strategies using Webpack, because despite the hype around newer JavaScript Bundlers like Vite or Turbopack, Webpack remains the backbone of complex enterprise applications in 2025.

The First Step: Stop Guessing, Start Measuring

You can’t fix what you can’t see. Before I touch a single line of configuration, I always run a bundle analysis. I’ve seen too many developers blindly adding plugins hoping for magic. My go-to tool is still webpack-bundle-analyzer. It gives you an interactive treemap of your bundle, showing exactly which NPM packages are eating up your budget.

I usually set this up as a separate script in my package.json so I don’t slow down my regular builds.

// webpack.analyze.js

const { merge } = require('webpack-merge');

const prodConfig = require('./webpack.prod.js');

const BundleAnalyzerPlugin = require('webpack-bundle-analyzer').BundleAnalyzerPlugin;

module.exports = merge(prodConfig, {

plugins: [

new BundleAnalyzerPlugin({

analyzerMode: 'server',

openAnalyzer: true,

}),

],

});When I ran this on my bloated project, I immediately saw that we were shipping three different versions of lodash and a massive localized date library we weren’t even using. Cleaning up those imports is step one, but the real gains come when we start squeezing the remaining code.

Implementing Aggressive Compression

This is where the magic happens. Modern browsers are incredibly good at inflating compressed files on the fly. While Gzip has been the standard for decades, Brotli is the superior algorithm for text-based assets like CSS and JavaScript. I prefer to generate both formats at build time. This allows the server to serve Brotli to browsers that support it (which is most of them) and fall back to Gzip for older clients.

I use the compression-webpack-plugin for this. It’s robust and integrates perfectly into the Webpack pipeline. Here is the configuration I use to generate both .gz and .br files.

// webpack.prod.js

const CompressionPlugin = require("compression-webpack-plugin");

const zlib = require("zlib");

module.exports = {

// ... other config

plugins: [

// 1. Generate Gzip files

new CompressionPlugin({

filename: "[path][base].gz",

algorithm: "gzip",

test: /\.(js|css|html|svg)$/,

threshold: 10240, // Only compress assets bigger than 10KB

minRatio: 0.8, // Only keep files if compression reduces size by 20%

}),

// 2. Generate Brotli files

new CompressionPlugin({

filename: "[path][base].br",

algorithm: "brotliCompress",

test: /\.(js|css|html|svg)$/,

compressionOptions: {

params: {

[zlib.constants.BROTLI_PARAM_QUALITY]: 11, // Max quality

},

},

threshold: 10240,

minRatio: 0.8,

}),

],

};I want to highlight the threshold setting here. I set it to 10KB (10240 bytes). Compressing tiny files often isn’t worth the CPU overhead for the decompression, and sometimes the headers required to serve the compressed file make it larger than the original. I find 10KB is a sweet spot for Web Performance.

Also, notice the Brotli quality is set to 11. Since we are compressing at build time (not on the fly), we can afford to use the most CPU-intensive setting to get the smallest possible file size. It might add a few seconds to your CI/CD pipeline, but your users save that time on every single page load.

Serving the Compressed Assets

This is the part that trips people up. I’ve seen teams set up the compression plugin, deploy the build, and then realize the browser is still downloading the uncompressed bundle.js. Why? Because the server doesn’t know it’s supposed to look for the .br or .gz versions.

If you are using a Node.js JavaScript backend with Express.js to serve your static files, you need middleware that checks for the compressed version first. I use express-static-gzip, which handles both Gzip and Brotli lookups automatically.

// server.js (Express)

const express = require('express');

const expressStaticGzip = require('express-static-gzip');

const path = require('path');

const app = express();

const distPath = path.join(__dirname, 'dist');

// Instead of standard express.static

app.use('/', expressStaticGzip(distPath, {

enableBrotli: true, // Look for .br files

orderPreference: ['br', 'gz'], // Prefer Brotli

setHeaders: (res, path) => {

res.setHeader("Cache-Control", "public, max-age=31536000");

}

}));

app.listen(3000, () => {

console.log('Server running on port 3000');

});If you are using Nginx or Apache, the configuration is different, but the concept is the same: use the Accept-Encoding header from the request to determine which file to serve.

Code Splitting: Don’t Load What You Don’t Need

Compression shrinks the files, but code splitting ensures you aren’t sending code that isn’t needed for the initial render. Modern JavaScript applications, especially Single Page Applications (SPAs), tend to bundle everything into one file. I prefer to split my vendor libraries (like React, Vue, or Angular) separate from my application logic.

Webpack’s optimization.splitChunks is incredibly powerful, though the documentation can be dense. Here is the strategy I use for most Full Stack JavaScript projects:

// webpack.prod.js

module.exports = {

// ...

optimization: {

runtimeChunk: 'single', // Extract Webpack runtime

splitChunks: {

chunks: 'all',

maxInitialRequests: Infinity,

minSize: 0,

cacheGroups: {

vendor: {

test: /[\\/]node_modules[\\/]/,

name(module) {

// Get the name of the package

const packageName = module.context.match(/[\\/]node_modules[\\/](.*?)([\\/]|$)/)[1];

// Create a safe name for the chunk

return npm.${packageName.replace('@', '')};

},

},

},

},

},

};This configuration creates a separate chunk for every NPM package. This might sound extreme, but with HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, the cost of multiple requests is negligible compared to the caching benefits. If I update my application code but don’t change my React Tutorial dependencies, the user’s browser doesn’t need to re-download React. It stays cached. This is a huge win for returning visitors.

Tree Shaking and Side Effects

Another area where I see developers leaving bytes on the table is tree shaking. Webpack tries to remove unused exports, but it needs help. I always ensure my package.json has the "sideEffects": false flag if my project is purely functional and doesn’t rely on global CSS imports or polyfills executing on import.

However, be careful. If you import a global CSS file like import './styles.css', setting sideEffects: false might cause Webpack to drop that import because it doesn’t see a variable being assigned. I usually configure it as an array to be safe:

// package.json

{

"name": "my-app",

"version": "1.0.0",

"sideEffects": [

"*.css",

"*.scss",

"./src/polyfills.js"

]

}This tells Webpack: “Go ahead and remove any unused JS exports, but keep these specific files even if they look unused.” It allows for much stricter dead code elimination.

Why Not Just Use Vite?

I hear this question constantly. “Why are you still configuring Webpack in 2025? Just use Vite!” And look, I love Vite. For a new Vue.js Tutorial or a small React app, it’s my default. But when I’m dealing with a legacy codebase, massive monorepos, or complex federation requirements, migrating to Vite isn’t a trivial afternoon task. It’s a massive undertaking.

Webpack is still the heavy lifter for enterprise. Understanding how to tune it is a skill that separates junior developers from senior engineers. You can’t always just swap out the build tool; sometimes you have to fix the engine while the car is driving.

The Results

After applying compression-webpack-plugin with Brotli, implementing aggressive code splitting, and enabling proper tree shaking, the results on my project were undeniable.

The original bundle size was 4.2 MB (uncompressed). After optimization:

- Parsed Size: 800 KB (Total JS)

- Gzip Size: 240 KB

- Brotli Size: 185 KB

We achieved a 95% reduction in the initial network transfer payload compared to the raw unoptimized build. The JavaScript Performance metrics on Lighthouse jumped from a 42 to a 96. The Time to Interactive (TTI) dropped by over 3 seconds on mobile devices.

Monitoring Over Time

Optimization isn’t a one-time task. It’s a habit. I set up performance budgets in Webpack to warn me if a PR accidentally bloats the bundle. If any asset exceeds 250KB, the build emits a warning. If it exceeds 500KB, the build fails.

// webpack.prod.js

module.exports = {

// ...

performance: {

hints: 'error',

maxEntrypointSize: 512000,

maxAssetSize: 512000,

},

};This forces the team to think about the cost of adding that heavy JavaScript Animation library or that massive icon set. Do we really need all of Three.js for a simple spinning logo? Probably not.

Final Thoughts on Build Tools

The ecosystem is always shifting. We have TypeScript Tutorial videos popping up daily about new runtimes like Bun or Deno, and JavaScript Tools like pnpm are changing how we manage dependencies. But the fundamentals of web performance don’t change. Less code over the wire equals a faster user experience.

Whether you are building a MERN Stack application, a Progressive Web App, or a simple marketing site, taking the time to configure compression properly is one of the highest ROI activities you can do. It doesn’t require rewriting your code; it just requires a better build configuration.

So, before you start rewriting your entire backend in Rust or migrating to a new frontend framework, check your Webpack config. You might be sitting on a performance goldmine just waiting to be compressed.