XSS Is Still Killing Your App: Here’s The Fix

I audited a legacy codebase last Tuesday that made me want to scream into a pillow. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of PHP 7, jQuery, and some haphazard React components bolted on top. The lead dev told me, with a straight face, “We’re secure against XSS because we strip script tags from all inputs.”

I typed <img src=x onerror=alert(1)> into their search bar. The alert box popped up. Silence in the Zoom room.

It’s 2026. We have self-driving cars and AI that can write poetry, but somehow, Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) is still lurking in the top vulnerabilities list. I see this constantly. Teams think they can outsmart hackers with a regex, or they assume their modern framework handles everything automatically. Spoiler: it doesn’t.

The “Big Three” Distraction

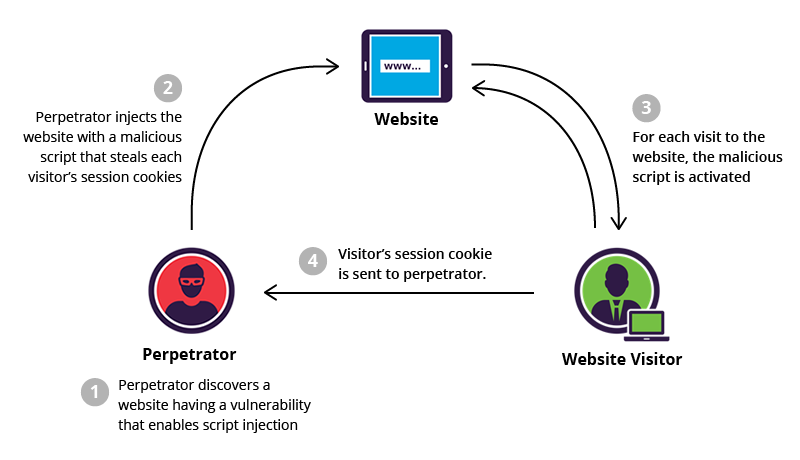

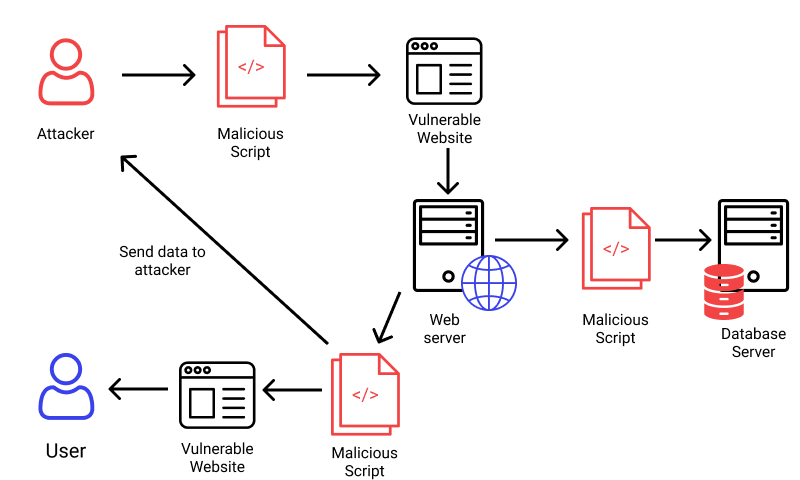

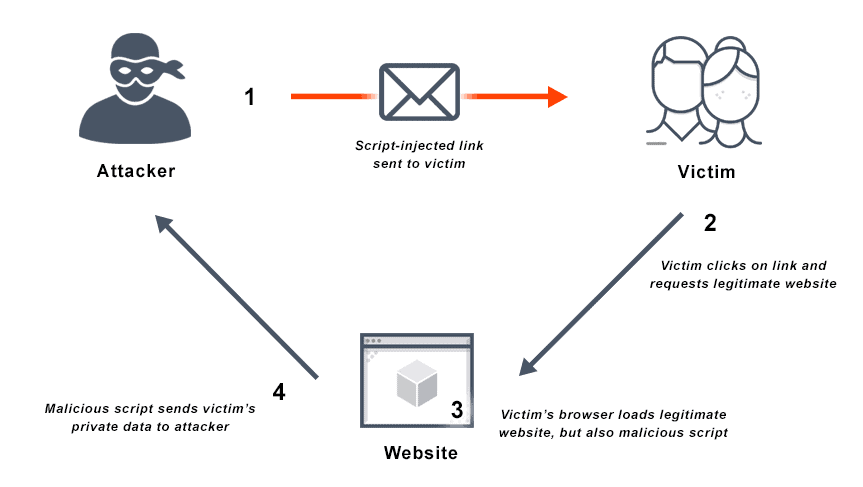

If you open any textbook, you’ll get the standard lecture about the three types of XSS: Reflected, Stored, and DOM-based. And yeah, knowing the difference is useful for triage, but when you’re actually building defenses? The distinction is academic fluff.

Here’s the reality: Data goes in, and executable code comes out. That’s it.

Whether that payload came from a malicious link (Reflected), a database record saved three months ago (Stored), or a weird URL fragment processed by client-side JS (DOM-based)—the fix is almost always the same. You have to treat all user data as radioactive until it’s rendered safely.

Stop Trying to “Sanitize” Input

This is where 90% of the devs I work with get it wrong. They try to clean the data when it arrives. They write these massive blocklists trying to catch javascript: or <script> or onmouseover.

Don’t do this. It’s a losing game. Hackers are creative. They’ll use base64 encoding, weird capitalization, or features of the browser you didn’t even know existed. Plus, if you aggressively sanitize input, you end up breaking legitimate data. Try explaining to a user named “O’Reilly” why they can’t save their profile because you blocked apostrophes.

The golden rule? Output Encoding.

You accept the input as-is (mostly), store it as-is, and then neutralize it strictly at the moment it gets rendered to the user. But—and this is the tricky part—how you neutralize it depends entirely on where you put it.

Context is Everything

I cannot stress this enough: Context matters. An encoding method that works in an HTML body will fail miserably inside a JavaScript variable.

1. HTML Body Context

This is the most common scenario. You’re dumping a string between tags, like <div>USER_INPUT</div>.

Here, you need to convert characters that have meaning in HTML into their entity equivalents. < becomes <, > becomes >, etc. Most template engines (Jinja2, EJS, Blade) do this automatically now. If you’re manually concatenating strings in 2026, stop it.

2. HTML Attribute Context

This is where I catch people slipping. Look at this code:

<input type="text" value="<%= user_input %>">If user_input is " onmouseover="alert(1), you just got owned. The browser sees the quote, closes the value attribute, and executes the event handler. To fix this, you must attribute-encode. This is more aggressive than body encoding; you have to escape quotes (", ') and whitespace characters too.

3. JavaScript Context (The Danger Zone)

This is the absolute worst place to put untrusted data. I see this pattern in legacy apps all the time:

<script>

var username = "<?php echo $username; ?>";

</script>If I set my username to "; alert('hacked'); //, the script executes. Standard HTML encoding doesn’t help here because the browser parses the script block before decoding HTML entities.

The only safe way to do this? JSON serialization.

Don’t build JS strings manually. Use your backend’s JSON library to encode the data, and make sure it escapes the forward slash / to prevent </script> breakouts.

<!-- The Right Way -->

<script>

var userData = <?php echo json_encode($user_data, JSON_HEX_TAG | JSON_HEX_APOS | JSON_HEX_QUOT | JSON_HEX_AMP); ?>;

</script>The “Modern Framework” Fallacy

I love React. I love Vue. They’ve done more for XSS prevention than a thousand security seminars. By default, they escape data before rendering. If you try to render <script> in JSX, React just prints the string literally.

But developers get lazy. Sometimes you need to render HTML (like from a rich text editor). So what do they do? They reach for dangerouslySetInnerHTML in React or v-html in Vue.

The name dangerouslySetInnerHTML isn’t a joke. It’s a warning label. If you use this, you are bypassing the framework’s protection. You are on your own.

If you absolutely must render raw HTML, you need a library like DOMPurify. It strips out the dangerous bits (scripts, event handlers) while keeping the formatting tags (bold, italics) intact.

import DOMPurify from 'dompurify';

const SafeComponent = ({ htmlContent }) => {

// Sanitize BEFORE rendering

const cleanHTML = DOMPurify.sanitize(htmlContent);

return <div dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: cleanHTML }} />;

};I reviewed a project last month where they imported DOMPurify but forgot to call it. They just passed the raw string. I wish I was kidding.

Content Security Policy (CSP): Your Safety Net

Even if you code perfectly, you’ll slip up eventually. Or a junior dev will. Or a third-party dependency will introduce a vulnerability.

That’s why you need a Content Security Policy (CSP). It’s an HTTP header that tells the browser which sources of executable scripts are approved. It effectively kills XSS by disabling inline scripts.

A strong CSP looks like this:

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.com; object-src 'none';This tells the browser: “Only run scripts that come from my own domain or this specific CDN. If you see <script>alert(1)</script> inside the HTML, ignore it.”

The catch? You have to stop writing inline JavaScript. No more <button onclick="...">. You have to move that logic into external JS files. It’s a pain to refactor legacy apps to support this, but honestly, the security payoff is massive. It turns a critical XSS vulnerability into a harmless rendering bug.

Final Thoughts

XSS isn’t going away. As long as we’re mixing code and data in the same channel (which is basically what HTML is), the risk exists. But we don’t have to make it easy for attackers.

Stop relying on regex. Stop trusting input. Use context-aware encoding, sanitize your rich text with a library that actually works, and for the love of everything holy, implement a CSP. If you do those three things, you’ll be ahead of 95% of the apps I audit.