Advanced Three.js: Implementing High-Performance Volumetric Rendering and Gaussian Splatting Techniques

Introduction to Modern Web Graphics

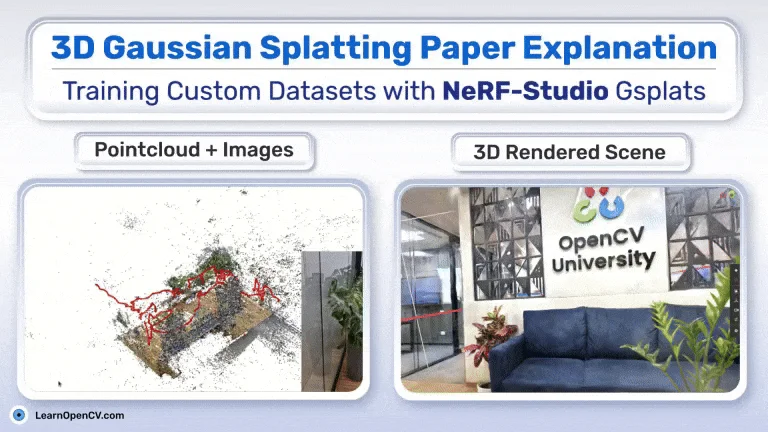

The landscape of web development has evolved dramatically over the last decade. What started as simple DOM manipulation has blossomed into a rich ecosystem capable of rendering photorealistic 3D experiences directly in the browser. At the heart of this revolution sits Three.js, a powerful JavaScript API that abstracts the complexities of WebGL. While many developers begin their journey with basic geometries and standard materials, the frontier of modern web graphics is pushing toward techniques like 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), point cloud visualization, and volumetric rendering.

As we move into an era dominated by Modern JavaScript (ES2024) and high-fidelity assets, understanding the low-level architecture of Three.js becomes crucial. We are no longer just placing cubes in a scene; we are dealing with millions of particles, complex sorting algorithms, and raw binary data processing. This article dives deep into the architecture required to build high-performance rendering engines within Three.js, focusing on techniques used in advanced point-based rendering, such as loading raw PLY data, implementing vertex pulling, and utilizing texture-based data storage.

Whether you are coming from a React Tutorial using React Three Fiber, or you are a vanilla JavaScript purist, these concepts will elevate your understanding of graphics programming. We will explore how to bypass standard abstractions to achieve 60 FPS performance with massive datasets, touching upon JavaScript Performance, Web Workers, and custom shader implementation.

Section 1: Data Ingestion and The PLY Format

In high-end 3D visualizations, particularly those involving 3D scanning or Gaussian Splatting, standard JSON or GLTF files can sometimes be inefficient for raw vertex data. The PLY (Polygon File Format) is often the standard for storing dense point clouds and splat data. To render millions of points, we cannot rely on the main thread to parse text. We must utilize JavaScript Async patterns, specifically Promises JavaScript and the JavaScript Fetch API, to handle binary streams efficiently.

The first step in a high-performance pipeline is loading this data into a JavaScript Typed Array. Unlike standard JavaScript Arrays, typed arrays (like Float32Array) provide a mechanism for accessing raw binary data, which is essential for WebGL buffers.

Here is an example of how to fetch and parse a binary PLY file header to prepare for data extraction. This approach avoids the overhead of text decoding for the bulk of the data.

async function loadRawPlyData(url) {

try {

// Using JavaScript Fetch API to get the raw buffer

const response = await fetch(url);

const buffer = await response.arrayBuffer();

// Create a view to parse the header

const decoder = new TextDecoder('utf-8');

let headerLength = 0;

let vertexCount = 0;

// Naive header parsing to find 'end_header'

// In a production environment, use a robust stream reader

const view = new DataView(buffer);

let headerText = '';

while (headerLength < buffer.byteLength) {

const char = String.fromCharCode(view.getUint8(headerLength));

headerText += char;

headerLength++;

if (headerText.endsWith('end_header\n')) {

break;

}

}

// Extract vertex count using Regex (JavaScript Regular Expressions)

const countMatch = headerText.match(/element vertex (\d+)/);

if (countMatch) {

vertexCount = parseInt(countMatch[1]);

}

console.log(`Loaded PLY with ${vertexCount} vertices. Header size: ${headerLength} bytes`);

// Return the body of the PLY (the raw data) and the count

return {

vertexCount,

dataBuffer: buffer.slice(headerLength)

};

} catch (error) {

console.error("Failed to load PLY:", error);

}

}

// Usage with Async Await

// loadRawPlyData('./model.ply').then(data => initScene(data));This code demonstrates JavaScript Best Practices for handling binary data. By manually parsing the header and slicing the buffer, we prepare the raw bytes for direct upload to the GPU. This is significantly faster than standard parsing libraries when dealing with hundreds of megabytes of data.

Section 2: Texture-Based Architecture and Vertex Pulling

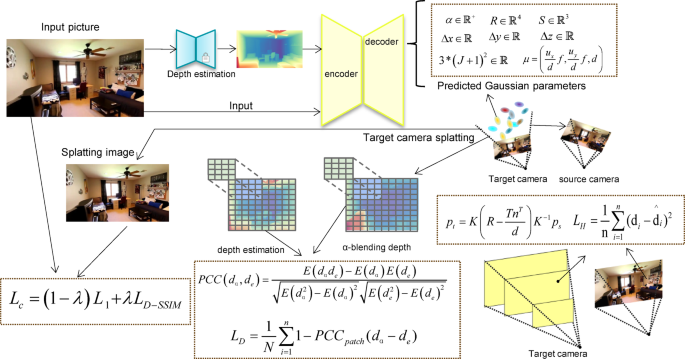

Once we have the data, the naive approach is to create a THREE.BufferGeometry and attach attributes for position, color, and scale. However, when rendering “splats” (oriented ellipses) or complex instanced geometry, we often hit limits on attribute counts or need more flexibility in how data is accessed. This leads us to a technique known as Vertex Pulling.

Apple TV 4K with remote – New Design Amlogic S905Y4 XS97 ULTRA STICK Remote Control Upgrade …

In a Vertex Pulling architecture, instead of pushing vertex attributes (like position) directly to the vertex shader via standard attributes, we store the data in Data Textures. The geometry itself is often just a “flat index buffer”—a simple list of indices (0, 1, 2, … N). The vertex shader then uses gl_VertexID (or an attribute equivalent) to “pull” the necessary position, rotation, and scale data from the textures.

This method is critical for techniques like Gaussian Splatting because it allows for complex data packing. For instance, you might pack a quaternion (rotation) and scale into a single texture fetch. This aligns well with JavaScript Optimization strategies where reducing CPU-to-GPU draw calls and bandwidth is paramount.

Implementing the Shader

Below is a conceptual example of a Three.js ShaderMaterial configured for vertex pulling. We use a DataTexture to hold our transform data.

import * as THREE from 'three';

function createSplatMaterial(transformTexture, numSplats) {

return new THREE.ShaderMaterial({

uniforms: {

uTransformTexture: { value: transformTexture },

uTextureSize: { value: new THREE.Vector2(transformTexture.image.width, transformTexture.image.height) },

uViewport: { value: new THREE.Vector2(window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight) },

uFocal: { value: new THREE.Vector2(1000, 1000) } // Example focal length

},

vertexShader: `

precision highp float;

precision highp int;

uniform sampler2D uTransformTexture;

uniform vec2 uTextureSize;

uniform vec2 uViewport;

uniform vec2 uFocal;

// We use an attribute for index because WebGL 1/2 support varies for gl_VertexID

attribute float splatIndex;

varying vec4 vColor;

void main() {

// Calculate UV coordinate in the data texture based on the index

float row = floor(splatIndex / uTextureSize.x);

float col = mod(splatIndex, uTextureSize.x);

vec2 texUV = vec2((col + 0.5) / uTextureSize.x, (row + 0.5) / uTextureSize.y);

// "Pull" the data

vec4 transformData = texture2D(uTransformTexture, texUV);

vec3 position = transformData.xyz;

// Simplified: assuming w component holds a scale factor

float scale = transformData.w;

// Standard projection logic would go here (omitted for brevity)

// In a real Splat renderer, you would compute the 2D covariance matrix here.

vec4 viewPos = modelViewMatrix * vec4(position, 1.0);

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * viewPos;

// Set point size for rasterization

gl_PointSize = scale * (uViewport.y / -viewPos.z);

vColor = vec4(1.0, 0.5, 0.2, 1.0); // Dummy color

}

`,

fragmentShader: `

precision highp float;

varying vec4 vColor;

void main() {

// Circular discard for point rendering

vec2 coord = gl_PointCoord - vec2(0.5);

if(length(coord) > 0.5) discard;

gl_FragColor = vColor;

}

`,

transparent: true,

depthTest: true,

depthWrite: false, // Essential for transparency blending

blending: THREE.CustomBlending

});

}This setup leverages Canvas JavaScript contexts via Three.js to perform operations that were traditionally the domain of native C++ engines. By using textures as data arrays, we bypass limits on uniform buffers.

Section 3: Advanced Sorting with WebAssembly (WASM)

One of the biggest challenges in volumetric rendering and 3DGS is transparency. To render semi-transparent objects correctly, they must be drawn from back to front. When dealing with a scene containing 1 to 5 million splats, JavaScript Loops and standard Array.prototype.sort() are simply too slow to run every frame (16ms budget).

This is where WebAssembly (WASM) and languages like Rust or C++ come into play. By offloading the sorting logic to a WASM module, we can achieve near-native performance. Furthermore, to prevent blocking the main UI thread (which handles the JavaScript DOM interactions), this sorting should occur in a Web Worker.

The Sorting Pipeline

- View Calculation: Calculate the camera’s view matrix in the main thread.

- Worker Transfer: Send the view matrix and the buffer of splat positions to the Web Worker.

- WASM Sort: The worker passes this data to a WASM function (likely implementing a Radix Sort).

- Index Buffer Update: The sorted indices are returned to the main thread.

- Geometry Update: The

THREE.BufferAttributefor indices is updated, andneedsUpdate = trueis flagged.

While we cannot provide a full Rust implementation here, below is the JavaScript glue code required to interface with such a worker. This fits into the JavaScript Design Patterns for concurrent programming.

// worker.js

self.onmessage = function(e) {

const { viewProjMatrix, positions, indices } = e.data;

// Simulate a heavy sorting operation (In reality, call WASM here)

// This is just a placeholder for the logic:

// 1. Project positions to depth

// 2. Sort indices based on depth (Radix sort preferred)

// Mock result for demonstration

const sortedIndices = new Uint32Array(indices);

// Post back the sorted buffer.

// IMPORTANT: Use Transferable Objects for performance to avoid copying memory

self.postMessage({ indices: sortedIndices }, [sortedIndices.buffer]);

};

// Main Thread Integration

class Sorter {

constructor(count) {

this.worker = new Worker(new URL('./worker.js', import.meta.url));

this.isSorting = false;

this.indices = new Uint32Array(count);

// Initialize indices

for(let i=0; i<count; i++) this.indices[i] = i;

this.worker.onmessage = (e) => {

this.indices = e.data.indices;

this.isSorting = false;

// Trigger a re-render or geometry update here

window.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent('indices-sorted', { detail: this.indices }));

};

}

sort(viewProjMatrix, positions) {

if (this.isSorting) return; // Don't choke the worker

this.isSorting = true;

// Send data to worker

// Note: In production, use SharedArrayBuffer if cross-origin isolation permits

this.worker.postMessage({

viewProjMatrix,

positions, // Ideally a Float32Array view

indices: this.indices

});

}

}This pattern ensures that your application remains responsive. JavaScript Tools like Vite or Webpack handle the worker bundling seamlessly in modern setups.

Section 4: Optimization and Best Practices

Apple TV 4K with remote – Apple TV 4K 1st Gen 32GB (A1842) + Siri Remote – Gadget Geek

Building a high-performance renderer involves more than just raw code; it requires adherence to JavaScript Best Practices and a solid understanding of the JavaScript API for WebGL.

Memory Management

When working with large PLY files and textures, memory leaks can crash a browser tab instantly. Always dispose of geometries, materials, and textures when they are no longer needed. In React Tutorial contexts (like React Three Fiber), use the dispose={null} pattern or rely on the library’s automatic unmounting cleanup.

Quantization and Compression

To reduce the GPU memory footprint, consider “SOGs quantization” or similar compression techniques. Instead of using full 32-bit floats for every property, you can pack data. For example, normals can be packed into two 16-bit integers, or colors into a single 32-bit integer. Spherical Harmonics (SH) coefficients, used for view-dependent lighting in 3DGS, are heavy; truncating them to lower degrees or compressing them is often necessary for web delivery.

Framework Integration

Apple TV 4K with remote – Apple TV 4K iPhone X Television, Apple TV transparent background …

While the core logic is pure Three.js, integrating this into a full application often involves a Full Stack JavaScript approach. You might serve the PLY files via a Node.js JavaScript backend (using Express.js) to handle CORS and compression (gzip/brotli). On the frontend, if you are using the MERN Stack, ensure that your 3D canvas does not trigger unnecessary React re-renders. Use refs to manipulate the Three.js scene graph directly for performance-critical updates.

Debugging

Debugging shader code and binary buffers can be difficult. Use tools like Spector.js to inspect WebGL commands. Additionally, ensure your code is robust against JavaScript Security issues, such as XSS, although this is less of a concern in WebGL logic and more relevant to how you fetch and sanitize URLs for your assets.

Conclusion

Mastering high-performance rendering in Three.js requires a shift in mindset from manipulating objects to manipulating data streams. By leveraging JavaScript Async for loading, Data Textures for storage, and Web Workers with WASM for computation, developers can bring desktop-class graphics to the web. The techniques discussed here—specifically vertex pulling and texture-based architecture—are the foundation of modern implementations like 3D Gaussian Splatting.

As you continue your journey, consider exploring TypeScript Tutorial resources to add type safety to these complex data structures, or look into JavaScript Build tools to optimize your WASM integration. The web is ready for high-fidelity 3D; the only limit is the efficiency of your code.