Service Workers Are Just Persistent MITM Attacks

Well, I have a confession – I used to hate Docker. But after spending my entire weekend debugging a client’s e-commerce site that was behaving… strangely, I’ve had a change of heart. Users were complaining that every third or fourth time they clicked a product link, they ended up on some shady “You’ve won an iPhone” landing page. And you know what? The server logs were clean, and the backend code hadn’t been touched since the Tuesday deploy. I was tearing my hair out.

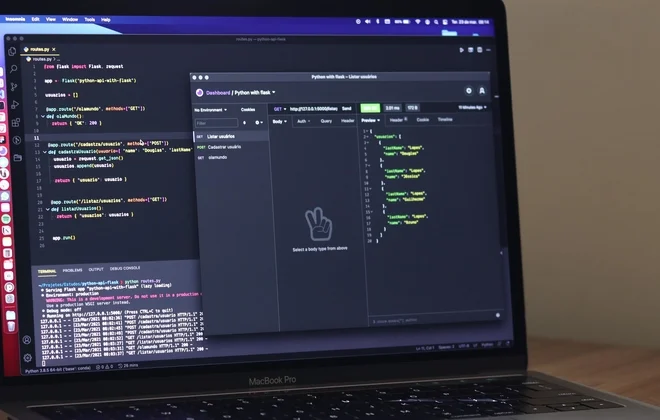

Actually, it wasn’t until I opened the Application tab in DevTools that I realized what had happened. We hadn’t been hacked. The users’ browsers had been hacked.

A rogue Service Worker was sitting there, quietly intercepting network requests and rerouting traffic whenever it felt like it. And the worst part? This persists even after the user closes the tab or restarts the browser. It’s the ultimate persistence mechanism, and we hand it to developers on a silver platter.

The Double-Edged Sword of “Offline First”

Look, I love Progressive Web Apps. But we need to be honest about what a Service Worker actually is: a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) proxy that lives inside the user’s browser. And if you have a Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability, or if you load a third-party ad script that goes rogue, they can register their own Service Worker. And once that worker is installed, they own the navigation flow.

The Anatomy of a Hijack

The attack vector is terrifyingly simple. The attacker doesn’t need to infect your server. They just need to run one line of JS in the victim’s browser to register a malicious file. And once that file is cached as the Service Worker, the attacker’s job is done. The script disconnects from the original vulnerability and lives on its own.

Why This is So Hard to Kill

The persistence model of Service Workers is aggressive. Even if you remove the malicious script code from your website’s HTML, the user’s browser already has the Service Worker installed. Unless you ship a new Service Worker to replace it (which is hard if the old one is blocking the update checks) or the user manually clears their storage, that zombie script keeps running.

How to Lock It Down

1. Content Security Policy (CSP) is Mandatory

If you aren’t using CSP in 2026, you’re asking for trouble. Specifically, you need the worker-src directive. This tells the browser exactly which domains are allowed to load scripts meant for Service Workers. According to the Mozilla Developer Network documentation, the worker-src directive “specifies valid sources for Worker, SharedWorker, or ServiceWorker scripts.”

2. The “Kill Switch” Script

Every PWA needs a kill switch. I now include this snippet in the main bundle of every app I build. It checks against a “safe list” of known good Service Worker filenames. If it sees something unexpected, it nukes it. The Mozilla Developer Network documentation on the ServiceWorkerContainer.register() method provides guidance on managing and updating Service Workers.

The Reality Check

Service Workers are powerful, but they operate with a level of trust that the modern web rarely justifies. We treat them like just another JavaScript file, but they are infrastructure. If you are building a PWA, don’t just copy-paste the registration code from a tutorial and call it a day. Audit your third-party scripts. Set your headers. And for the love of code, monitor what is actually running in your users’ browsers. The web.dev guide on Progressive Web Apps provides best practices and recommendations for building secure and reliable PWAs.